T

hey are people. They are not wanderers. They are not drifters. Every person without housing in any part of the world has a story, which can be anyone’s story. They need the same thing you do, but they don’t have it.

“People think that people without housing is only related to the person who sleeps on the bench in the park, the one who sleeps in an abandoned building, but the reality is that it is much more complex.”

An essential part of the efforts to address the problem of people without housing seeks to create awareness that it is not a situation that is foreign to many people. Dr. Juan Nazario, professor of the Doctorate Program in Clinical Psychology at Albizu University, explains that it is a complex problem.

“People think that people without housing is only related to the person who sleeps on the bench in the park, the one who sleeps in an abandoned building, but the reality is that it is much more complex. A person without housing can be someone who has a home but does not have the necessary utilities such as water, electricity, etc. It can be someone in a transitional shelter as a victim of domestic violence; the person in a shelter is considered a person without housing for that period. Likewise, the person who sleeps in the car or in any place not suitable for spending the night and not suitable for the dignity of the human being.”

The concept has been extended to consider the population’s vulnerability factors, as explained by Josué Maysonet, executive director of Fondita de Jesus. This nonprofit entity has been serving the basic needs of people without housing people for 36 years. “There is always the concept of people who are unemployed, who have lost their homes for different reasons, people with situations of substance abuse, victims of gender-based violence, people who their families have rejected for being from the LGBTQIA+ community. However, new profiles have emerged within people without housing. We see this process of gentrification in metropolitan areas, where there has been a housing shortage and inflation in rental costs. The same happens with utilities, which when they increase significantly, some people cannot afford these expenses and end up on the street.” The new needs faced by the elderly are also now being looked at, indicates Maysonet. “The pandemic, the state of mental health, and the basic needs of this population have led them to abandonment. Although they have a roof over their heads, it is not a safe place, and they end up on the street. They are not being cared for by their relatives or any agency.” Dr. Nazario warns that it is crucial to review public policies to temper them with the reality of people without housing, which should be addressed as a problem of lack of access to a safe home or basic needs. Therefore, they advocate for avoiding using the term “homeless” and seek to educate people to overcome myths. “It can have a stigmatizing connotation because people can associate it with derogatory words. For example, before, drifter was used a lot. However, we are talking about a much more complex phenomenon. Some elements can lead anyone to that experience of being without housing, which is why we prefer to move it to a more inclusive and dignified language, and social justice”, explains Dr. Nazario.

“It is very important to give the students who are in the process of training a space for them to understand vulnerable populations.”

Albizu University has worked on various public policy formulation projects and has allied with community-based entities to educate about people without housing. Direct service efforts with students have also been developed and implemented. “It is very important to give the students who are in the process of training a space for them to understand vulnerable populations. Seven years ago, we created Recinto Solidario, an organization where students are trained with health models to work with people without housing and their intersectionality. This training involves people with mental, physical, or substance abuse problems. The students are trained with this model, and we work on risk reduction strategies. It is an element of transformation, not only for the people who receive our services, but also for our students,” explains Dr. Nazario. Dalmary Mirabal is part of the initiative and describes it in simple terms: “it is to see those needs that they require, and we go with them, instead of them going to the psychologist, the psychologist goes to where they are.”

Everyone agrees that much work is ahead to attend to even the most urgent needs. “We tend to think that a roof will solve all their problems,” says the director of La Fondita de Jesús. “The reality is that assisting people without housing is done on a case-by-case basis to address specific needs. Structures are needed to locate these people, but at the same time, there is guidance in services and attention to their needs and mental health. There is also a need for more empathy from government institutions and greater collaboration from hospitals and the security system. Finally, education is needed at all levels.” For this reason, the Fondita de Jesús has expanded its efforts to reach communities at risk, since even when people have a roof over their heads, “we don’t know if it is a safe space. Sometimes it is merely a lack of knowledge that the person has of their rights, what agencies they can reach, what door I can knock on,” explains Joanly Rodríguez, director of Community Development Programs at La Fondita de Jesús.

To educate, you must make the problem visible

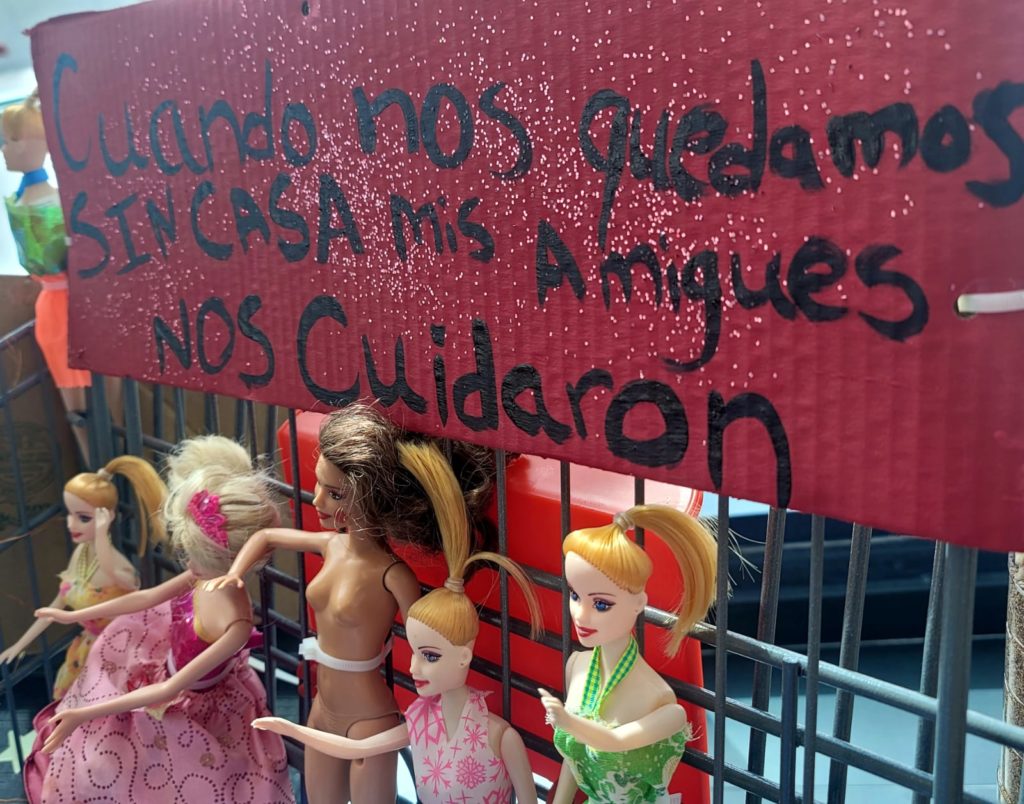

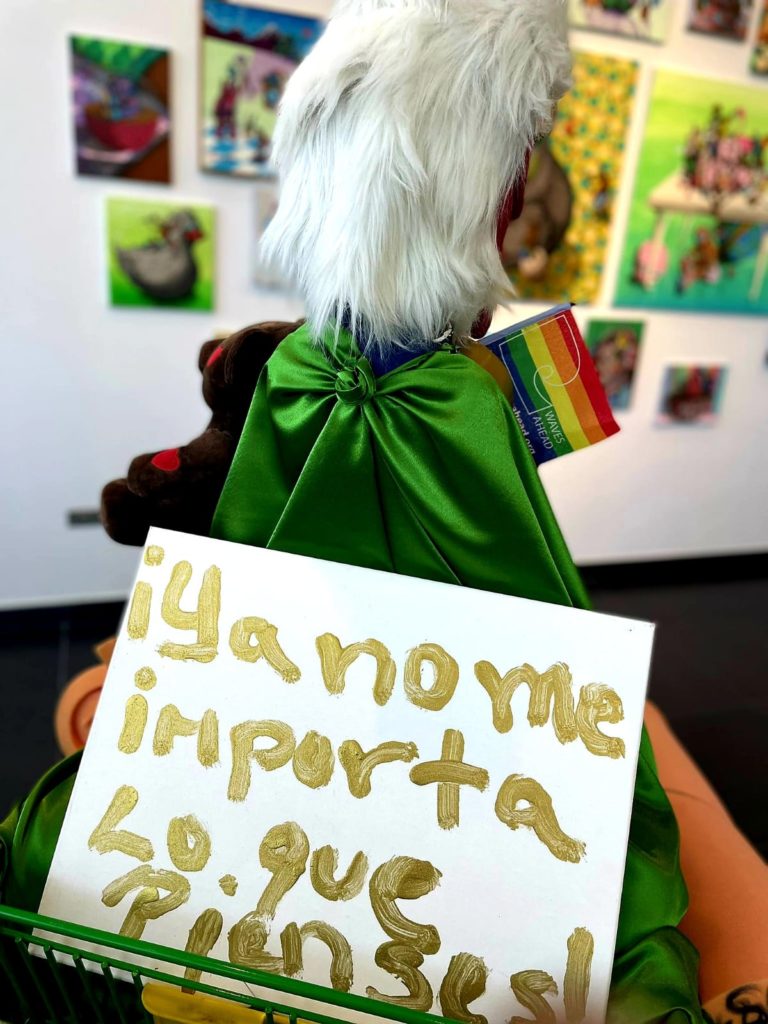

Albizu University and Fondita de Jesús joined forces to present Vehicles and Bridges, a collection of shopping carts that carry symbols, objects, and real stories of people who have been on the streets and have begun the path to reintegration. The carts are a creation of artist José Luis Vargas, in a collaboration between the Miramar Museum of Art and Design and the Fondita de Jesús.

“Vehicles and Bridges arises from this wonderful project of the Fondita de Jesús Social Justice and Equity Program, which works with public policy issues that help vulnerable people. Our participants, whom we call street speakers, work on education efforts in different forums. They spread the message: ‘I was in the street, I went through all these sudden changes, and I achieved community reintegration through alliances, the Fondita de Jesús, and other resources”, says Maysonet.

To understand this problem, it is necessary to know that no one is on the street because they want to. But you also must recognize that it can happen to anyone. Dr. Nazario explains this: “Any of us can (have) an element of vulnerability at some point in our lives that makes us fragile, and we could have the first episode of being without housing. We are in a historic moment due to economic issues, Covid-19 (… ) social crises that have a psychological reflection, and problems with access to health services and housing. This puts us in a situation of vulnerability. The reality is that each of us could be at risk, which is why it is so important that citizens, in general, understand what people without housing are and that we can all contribute to reducing this phenomenon.”